“MADE PICTURESQUE BY THE COSTUMES”: CLOTHING OF THE HOLY LAND COLLECTED BY FREDERIC CHURCH

An excerpt by Lynne Zacek Bassett, “Costume & Custom” Exhibition Co-Curator

Frederic, while expressing great admiration for the landscape, was conflicted about the native Middle Eastern people. While he considered the Bedouins “picturesque,” he also repeatedly described them in his diary and letters as dirty, savage, lazy, and dangerous. Beyond the meat, milk, and fur provided by their animals, the Bedouin also historically made a living by raiding caravans and villages, and extracting payment from such groups in exchange for protection.9 Extortion was still sometimes their practice in the nineteenth century.

Isabel noted in her diary the experience of the Jeromes10:

“ . . . these terrible Bedouins threatened to take the life of the dragoman if he did not give them more bakceesh [baksheesh]—So they were compelled to give the wretches an enormous sum in addition to what they had already given.”11

Dragomen acted as guides, interpreters, and often protectors for tourists in the Middle East. While the roughness of the impoverished Bedouin dismayed Church, he very much admired his dragoman Mikayel El Heny, who guided him on a two-week side trip to Petra (in modern-day Jordan): “One thing is evident— A party who comes here should have a thoroughly tried and reliable Dragoman otherwise the trip must be a failure and as has sometimes happened be even dangerous.” 12 The gray wool suit (fig. 5) with the full “sirwal” trousers resembles that worn by the guide who holds the head of Church’s camel in the photograph taken during his journey to the Holy Land (fig. 4). Such suits

were readily distinguishable from the clothing of the Bedouin, who did not wear fitted jackets, and set the dragoman apart as a man from a village or urban setting— and thus, more respectable to their Western clients.

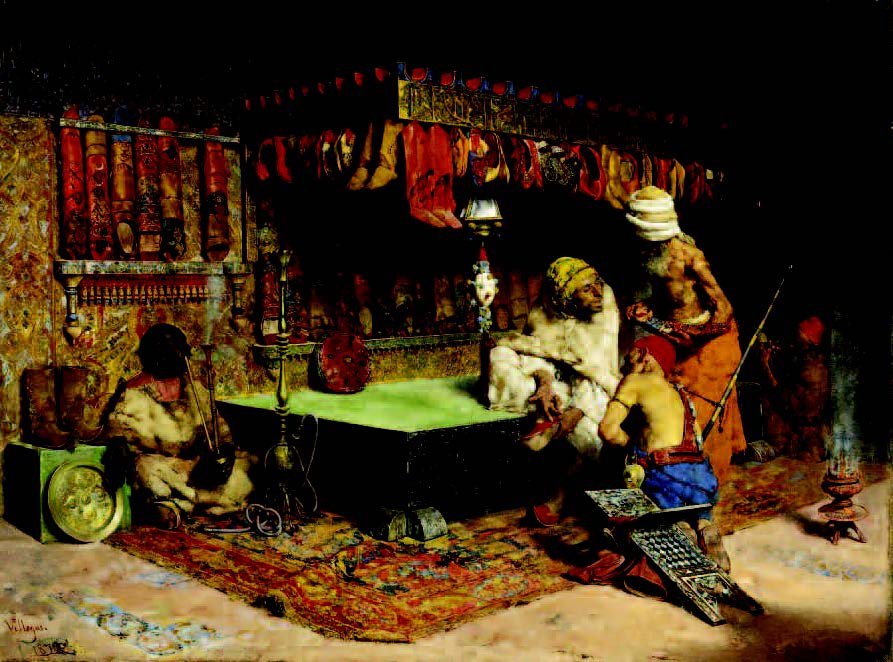

Frederic and Isabel shipped home multiple crates of objects that Church called his “pickings”13 for furnishing their home and property, which would eventually be called “Olana.” Writing from Rome to his friend and patron, William H. Osborn, Church anticipated getting home to check his crates, which had been shipped ahead from Constantinople: “I think it would amuse you and Mrs. Osborn to see the medley in the box—for there are rugs—armour—stuffs—curiosities, etc., etc., etc., crowded in together and some of the other boxes have old clothes (Turkish) stones from a house in Damascus, Arab spears—beads from Jerusalem—stone from Petra and 10,000 other things.”14 Church gathered these items from a variety of sources, including hawkers, antiques dealers, and bazaar merchants. Isabel described the bazaars of Damascus in her diary as long streets covered with either a stone roof or a wooden lattice with “vines trained all over, very pretty. Bazaars seem interminable, whole streets sometimes devoted to selling one article….”15 But she complained of the “exhorbitant” [sic] prices aggressive peddlers demanded of tourists for their wares. Although the scene in The Slipper Merchant, 1872 by José Villegas Cordero (fig. 6) depicts Morocco, Frederic and Isabel would have experienced similar shopping situations. Church brought back yellow boots and curled-toe shoes (checklist 33, 34, 35, 40) like those offered by this “slipper merchant.”

To reserve your copy of the “Costume & Custom” exhibition catalog, Email.