“A Healthy Kind of Discomfort”

By Sean E. Sawyer, Ph.D., Washburn and Susan Oberwager President

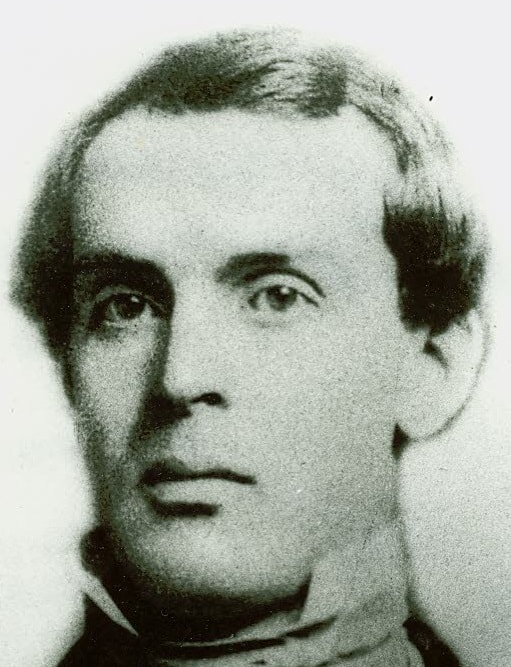

From May through October this year Olana will witness a confrontation between two of our country’s most prominent artists; one, Frederic Church, who achieved fame 150 years ago, and another, Teresita Fernández, who is reaching it today.

This has come about through a collaboration between The Olana Partnership and the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, one of the world’s most important collections of Latin American art. Together, we have invited Fernández to respond to Church’s artistic legacy by drawing upon the Cisneros’ collections, as well as our own, to create new work. The result is OVERLOOK: Teresita Fernández Confronts Frederic Church at Olana, an immersive exhibition that centers on three large-scale installations by Fernández and puts visitors “into this situation where there is a healthy kind of discomfort,” in her words. [1] I won’t discuss Fernández’s specific artistic goals here, as I hope you will come see for yourself, and, instead, I want to explore why The Olana Partnership, as stewards of Frederic Church’s legacy, would want to put visitors in this situation.

In his lifetime, Church actively sought international fame and the broad audiences it brought. In March 1863 a New York newspaper reported that:

“A new picture by Mr. Church is as considerable an event in the world of art as a new novel by Victor Hugo, or a new poem by Tennyson would be in the literary world. He has proved himself a master and an elaborate work from his easel is certain to represent the highest contemporary development of American art.” [2]

Indeed, it was this startling success, much of it achieved through his immersive “great painting” exhibitions, that funded his creation of Olana over 40 years.

In achieving fame and fortune, Church also engaged in artistic exploration, both literally in his travels from the Andes, to Arctic ice fields, to the Mideast, and metaphorically in his creation of emblematic landscapes that are more proto-Cubist collage than topographic renderings. Church reached the pinnacle of fame with Heart of the Andes in 1859, and one of the most evocative descriptions of the experience of viewing it was given by Mark Twain:

“You will never get tired of looking at the picture, but your reflections –your efforts to grasp an intelligible something–you hardly know what –will grow so painful that you will have to go away from the thing, in order to obtain relief. You may find relief, but you cannot banish the picture–It remains with you still.”

So, psychological discomfort brought about by challenges to the received patterns of perception characterized Church’s work as a contemporary artist. Here we are firmly in the realm of Fernández’s “healthy discomfort.” The most meaningful and contemporary art – of any period – engages and challenges us as viewers; it rouses us from our comfort zone and leads us to expand our mental and aesthetic horizons. Ultimately, its success is marked by its power to endure through time. Witness Church’s “great paintings” that are now the centerpieces of major collections across the country. This is why contemporary art and the inherent discomfort it often stimulates are at the center of The Olana Partnership’s goals in creating exhibitions at Olana.

This is a very recent turn of events. It began with Groundswell, a day-long presentation of site-specific works in sound, text, and movement done in collaboration with Wave Farm from 2013 to 2015 and installed in the landscape along Ridge Road. However, the embrace of contemporary art at Olana came with River Crossings: Contemporary Art Comes Home, the major exhibition undertaken with the Thomas Cole National Historic Site in 2015. River Crossings was the vision of Stephen Hannock, the renowned artist who is a member of our National Advisory Committee. Hannock threw all his artistic passion into the project and succeeded in bringing works by some of the world’s most recognized artists, including Maya Lin, Chuck Close and Cindy Sherman, to be exhibited in the historic interiors at the Cole House and Olana. The juxtapositions were startling and newsworthy, including articles in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal and a segment on CBS Sunday Morning. Also, attendance went up that season, although the demographic profile of the average visitor did not shift notably; that will come with repetition and more outreach.

As we launch our collaboration with Teresita Fernández and the Cisneros Collection this spring, we anticipate mixed reactions and welcome the dialogue that the “healthy discomfort” of contemporary art that engages with the issues of our day brings. Fernández’s installations raise questions of identity that are extraordinarily timely. As she says in The Art Newspaper, “It seems particularly relevant to me in this moment: who gets to define American art and who is excluded? The United States is the only country that uses America as though it’s exclusive. Throughout Latin America, we say ‘Americas’. This is a way of expanding what we think of as the American landscape.”

I can see Frederic Church climbing the Andes or crossing the Negev, smiling broadly.

[1] Julia Halperin, “Teresita Fernández wants to change the way you look at American landscapes,” The Art Newspaper, March 2, 2017.

[2] The New York Leader, March 21, 1863.

To read the recent article in ArtNewspaper, click here.